1995-2024. El fotógrafo Jordi Baron, gracias a la profesión de anticuario de su familia, tiene un acceso único y privilegiado a un mundo muy privado: el interior de muchas casas de Barcelona.

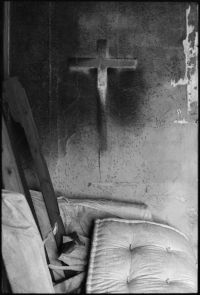

Cuando el autor llega a estos pisos, sus habitantes han fallecido recientemente, los familiares han repartido parte de la herencia y es entonces cuando quieren vender todo lo que queda en la vivienda. Otras veces, si hay desacuerdos familiares o si se trata de familias acomodadas, los pisos pueden permanecer cerrados durante mucho tiempo, a veces durante años, atesorando toda la memoria en su interior. Pero eso no significa que estén abandonados, sino simplemente cerrados, dormidos, hasta que llegue el día en que los propietarios decidan venderlo todo.

Las fotografías de Jordi Baron abordan todo el proceso de vaciado de pisos y casas, principalmente ubicados en el Eixample y el casco antiguo de Barcelona, donde sus herederos han ido vendiendo todo: primero el contenido y luego el continente.

Cada uno de estos pisos —muchos de ellos inmensos— ha sido luego dividido en tres o cuatro apartamentos con el objetivo de ser utilizados, en la mayoría de los casos, para alquiler turístico. Se trata así de la foto-finish de una memoria burguesa que ha durado unos 120 años, y el nacimiento de un nuevo fenómeno del que sufren muchas ciudades: la gentrificación. Un drama imparable que expulsa a los residentes debido al aumento del precio de la vivienda.

El autor, que trabaja como arqueólogo de interiores, ha estado documentando fotográficamente todos estos pisos de la ciudad de Barcelona durante unos 20 años, con el objetivo de rescatarlos instantes antes de su desaparición. Paisajes efímeros y muchas veces desolados, recuerdos personales en el suelo, ropa, libros, documentos… y es en esos momentos de cambio, de movimiento, donde se toman estas fotografías. Sin mucho tiempo, con luz natural, mientras los operarios y transportistas están ocupados desmontando camas, lámparas, arrastrando y embalando muebles que seguramente no se habían movido de su sitio en más de 80 años.

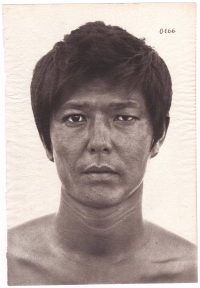

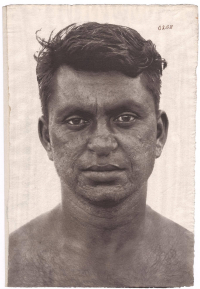

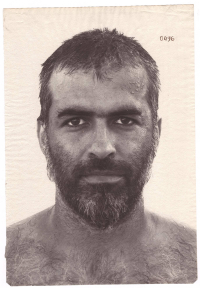

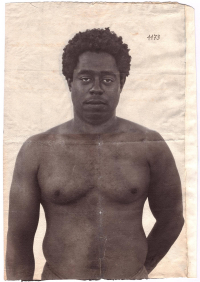

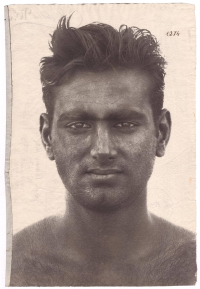

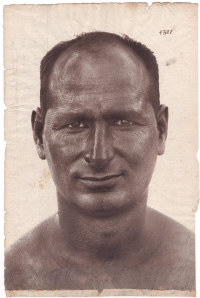

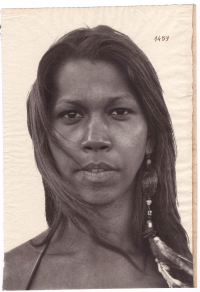

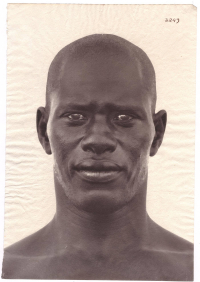

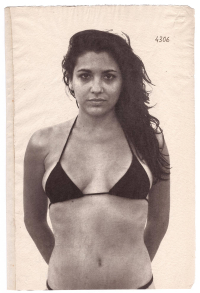

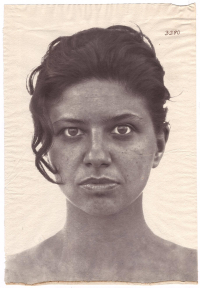

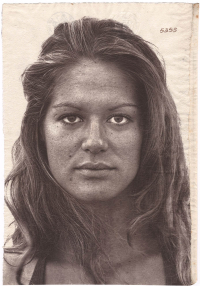

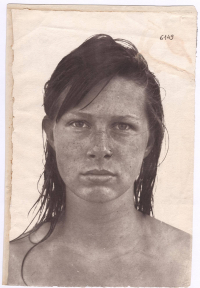

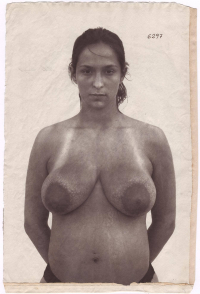

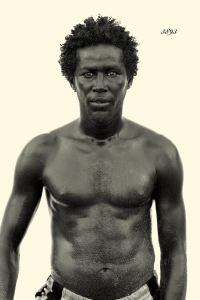

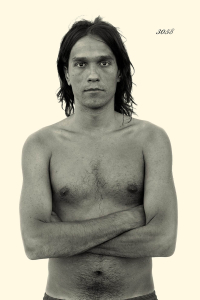

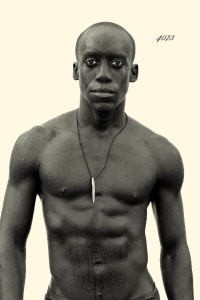

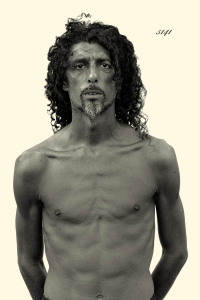

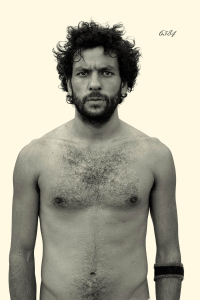

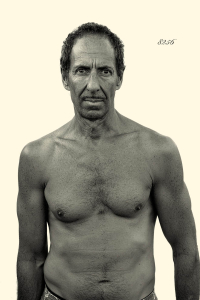

Las diferentes formas de mirar y representar al «otro», al extranjero, en el retrato fotográfico y dentro de la historia de la fotografía, son muy diversas. Pero cuando se trata de retratar a individuos lejanos, donde el idioma, la cultura y las diferencias entre el fotógrafo y la persona retratada son tan grandes, existen muchas interpretaciones posibles. Y esto es precisamente lo que implicaban las primeras expediciones científico-fotográficas que, a mediados del siglo XIX, viajaban a países exóticos y lejanos como Sudamérica y África —lugares que en muchos casos aún eran prácticamente desconocidos— para realizar inventarios o archivos antropológicos de las personas que habitaban esas tierras.

Más que reconocer una cultura primitiva como parte de una realidad diversa, el público de la época interpretaba esos retratos desde la distancia que separa la civilización de la barbarie. Es decir, todo lo que no es el hombre occidental se consideraba primitivo, inculto y salvaje.

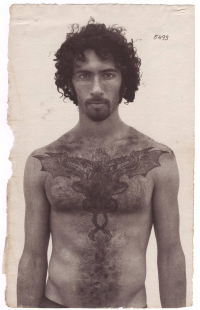

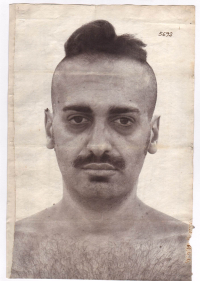

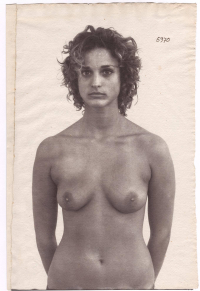

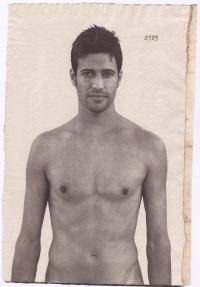

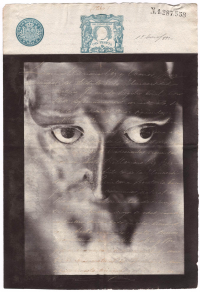

La serie fotográfica Archivo antropológico. Barcelona 2006–2010 pretende ser un inventario-registro de personas encontradas al azar en un mismo lugar y ciudad (en este caso, una esquina de la playa de Barcelona) y ofrecerles un tratamiento global inspirado en aquellos primeros fotógrafos científicos, donde la identidad de cada personaje se reduce a un simple número de registro en cada fotografía.

Se trata de tipos anónimos y catalogados, donde la diversidad confirma los grandes movimientos humanos de nuestro tiempo, muy lejos de lo que ocurría en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, cuando la búsqueda de lo “diferente” era uno de los principales argumentos de las experiencias viajeras.

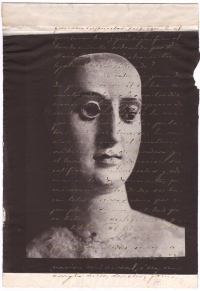

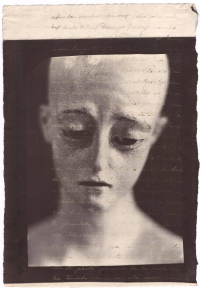

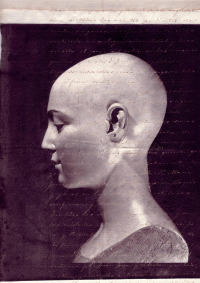

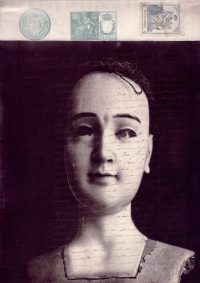

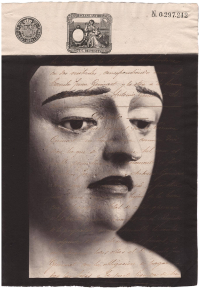

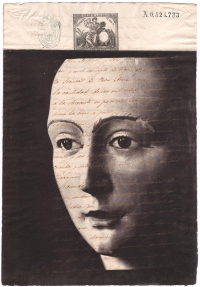

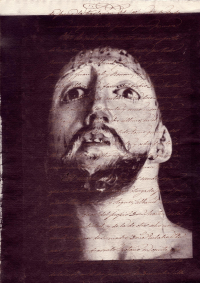

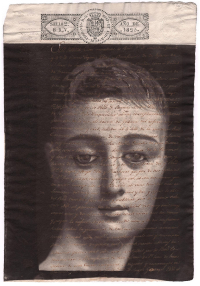

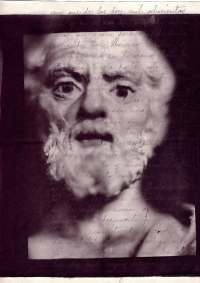

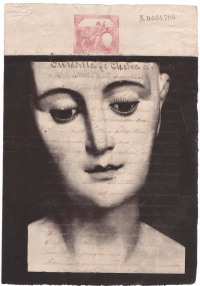

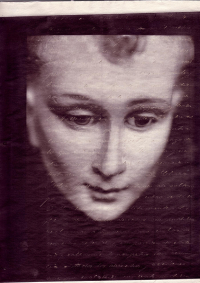

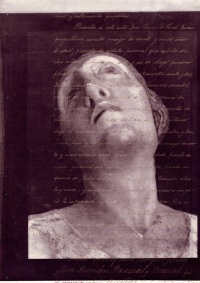

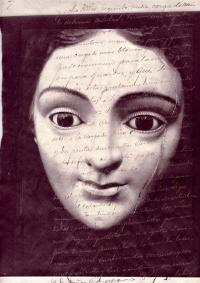

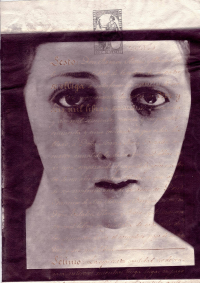

La adoración de dioses y santos ha estado presente en la humanidad desde tiempos antiguos. Si miramos atrás, una gran mayoría de personas conservaba esculturas de santos populares y vírgenes en sus hogares para su veneración. Pero esta función de la imaginería religiosa puede verse hoy en día alterada, principalmente, por el paso del tiempo, el relevo generacional o las modas, y su uso ha sido a menudo olvidado o reemplazado por una función meramente decorativa.

La erosión de los años ha despojado a estas figuras de todo lo superfluo, convirtiéndolas en esculturas toscas. Los ropajes se han podrido y han sido desechados, o han sido mutilados, o han quedado sin policromía. Pero lo más importante: han perdido su función original, la idolatría. Es entonces cuando se convierten en rostros incomprendidos y enigmáticos, viejos ídolos caídos, anónimos y desconocidos.

Toda la colección de fotografías de esta serie está impresa con una técnica del siglo XIX llamada vandyke brown y virada al oro. Y el tipo de soporte elegido: antiguos documentos manuscritos del siglo XIX, donde los rostros de las imágenes aparecen superpuestos con los textos. Textos que, al no tener relación directa con las imágenes, también han perdido su función original y se convierten en discursos vacíos de significado, donde cada obra funciona como una antigua reliquia.